Daniel Shen Smith is a barrister and Youtuber, here he talks to Jason about mediaeval conflict resolution, modern conflict resolution and what to do if someone’s pig escapes into your orchard.

Jason Kingsley 0:01

The law is often seen as a complex and impenetrable subject, and quite frankly, it is. For Dickens, it was all dusty books and interminable lawsuits, some of which lost whole fortunes. For most of us, the closest we get is blind clicking through pages of terms and conditions every time we instal something. However, law wasn’t always like that. With trial by combat and trial by ordeal, the legal system in the Middle Ages could be quite exciting and exacting and painful. To give us a different perspective, today I’m talking to Daniel Shen Smith, who combines the disciplines of martial arts with being a practising barrister. He also has his own YouTube channel called Black Belt Barrister.

Welcome to future imperfect.

Daniel Shen Smith 0:54

I suppose the best place to start is I’m an entrepreneur at heart, and always have been. And I would say entrepreneurs are born not made, I think it really is something of substance. So as a result, I’ve never worked for anybody else. I’ve always been in business for myself. And I made that decision very early on, sub-10 years old, I suppose. So whilst being at university I always had my own businesses. For the better part of eight to ten years now, one of those is a barristers’ chambers. More recently, a law firm authorised by the Bar Standards Board, which was a fairly pioneering law firm. And of course, I’m a barrister. So whilst I do all of that, in the background, I’ve always done martial arts. So that’s probably the best part of 30 years, which is probably something you’ve also come across, interestingly, is the first thing anybody ever say to me when they’ve looked me up online is that I’m a black belt as well. And they find the two are an interesting mix that go together. So hence, the two YouTube channels, which is Black Belt Secrets, and more recently, Black Belt Barrister, both of which were brought about to help people because in the martial arts world, I had lots of people coming for one to one classes, and obviously, there’s only one of me and only so much time. So I turned to YouTube, and it reached thousands of people. And now I’d like to do the same with law, hence Black Belt Barrister, it’s working very well so far.

Jason Kingsley 2:14

Yes, I find that interesting, because in many ways, you represent an old concept. And I do to a certain extent, as well, this concept of not having to overly specialise in just one thing. You can bring together two or more or multiple aspects and it’s almost a renaissance concept, the idea that you can specialise in more than one thing, and it gives you a different perspective. How do your martial arts aspects and approaches reflect into your law practice?

Daniel Shen Smith 2:46

I think I can relate to both of those statements and questions in one really. I think it’s the work ethic and the skill base that one can bring to any ability, to any field of work. Hence, whilst martial art is obviously very different to law, the approach can be very much the same in that you have to have this work ethic, relentless work ethic, and understand that it’s going to take a long time before you really get anywhere. The old adage is that the real training starts at black belt. I really believe that because the first sort of three or four years or however long, depending on the art, it takes you to get a black belt, I think the real training starts there. And obviously, for me, that was many years ago, circa 1997, or something, I got my first black belt.

Jason Kingsley 3:36

One of the interesting things I think about knowledge in general – and we’ll get onto the sort of more of the subject of the mediaeval world and trial by combat in a bit -but one of the things I think is fascinating about studying something is this sort of knowledge appreciation curve. When you start out, you think I kind of know quite a lot about this. Then as you study more, you realise you really don’t know much about the subject at all. Then you climb back out of this valley of despair, where you realise the subject so enormous, you don’t stand a chance and you start to go, actually, I am slightly competent at this now. And then you realise that, you know, you are actually almost an expert. It’s the same with the physical practice of martial arts in a variety of different ways, you know, might be the sort of more traditional Eastern martial arts or my own personal area of the mediaeval stuff. But it’s sort of the same in science, which is largely my background. I imagine it’s the same as law. There’s a process you go through.

Daniel Shen Smith 4:34

Absolutely, yes, as you were saying that I can relate very specifically to the law degree. Many years before I did a law degree, I did A-Level Law. I would probably say the first year of a law degree is very similar to A-Level Law. So I went in and it was a sort of double effect of, Yes, I know quite a bit about this. But by year two, then you realise actually, I need to spend quite a lot more time reading otherwise I’ll get lost in the material and you literally read law – there’s no exaggeration. Then by year three, you sort of get on top of how to do it. What really brought it down for me was the bar course. One of the tutors said at the very beginning, This will be the most intense year – or rather nine months – of your life. They weren’t kidding. It really was. And it comes back to those skills again, because that course really was teaching you the skills to be able to research something and to explore something, examine something, and then really understand it and apply it and analyse it. So it really comes down to those skills. And it does take time, it takes a lot of time and commitment.

Jason Kingsley 5:40

There’s this concept of analysis. Is it called “construal”? A way you construe an argument? Or is that something that judges do? You go through and try and get rid of the He Said, She Said stuff which every body always has? And you go, Right! How do we break this down into sort of a logical thread? Is that something?

Daniel Shen Smith 6:02

Yes, indeed, there’s lots of ways of looking at that. And I think it’s called the glaziers test, with various ways of looking at different things. So you can draw inferences, you can make assumptions. And it can make you look at things in very different ways. So, you know, someone can tell you a set of facts or a scenario. And you can tell that they’ve made an assumption based on those facts. But I might say, well, actually, you can’t assume that this person knew that this was the case. You can’t assume that they did that just because of something else. You may have drawn an inference, you may have made an assumption. And those are where the real arguments lie. So someone might think that something is done in bad faith, for example, but whereas you might say, well, just because they knew of the existence of something doesn’t make it bad faith, it’s all down to the intention. So yes, there’s lots of different ways of analysing those facts and arguments and the understandings. And I think that brings us on when I was doing some reading for today, about trial by combat, to trial by ordeal. The beliefs at that time were what governed those practices. There’s absolute belief that there is an Almighty watching over and that the right outcome will prevail. In a roundabout way, everybody that has religious beliefs in one form or another, live by those rules today. They still believe that there is an Almighty and that justice will prevail overall.

Jason Kingsley 7:35

Yeah, it is interesting, because I was trying to do some research as well. And I was wondering, what proportion of the population actually thought trial by combat was sensible way of solving it and or what proportion of the thought it was a load of nonsense, but it was the way society did it, therefore, I better keep quiet or I could get into trouble. And the trial by combat I’ve read about – particularly the later one in France – it’s very famous. It was typically for nobility, for the fighting class, and it ties in with the notions of chivalry and might is right. I wondered whether it shades into the idea of duelling as well, this masculine approach to, Let’s have a fight, but let’s have it organised properly. Not just an ordinary brawl, we want a proper decent gentleman’s fight on the common. Duelling is presumably illegal, technically, today, and was presumably banned, or was it never banned? It just sort of fell out of favour?

Daniel Shen Smith 8:37

Yes, well, there’s a number of aspects to that. I mean, the overriding principle today is you cannot consent to serious harm, of course, unless it’s for medical purposes, and, and things like that. Even engaging in sports, you know, such as boxing, rugby, you know, one accords to the rules of the game. And, you know, you’re not consenting to anything beyond that. So that that’s the general position. And, of course, you know, abolition of the death penalty. And even for things such as treason and piracy with violence, it wasn’t until much more recently – 1998 without checking – but lots of these things are sort of more gradually being phased out over time than one might think. But going back, and when I was doing the reading, it does seem that there was this belief that if we take, for example, trial by combat or trial by battle, that the victor was right, it was watched over by God, and therefore must have been innocent because he won the fight. That was even the case if his accuser had elected a champion in their stead. And that might be even against the government or an organisation.

Jason Kingsley 9:48

So sometimes these rules seem to fizzle out and then finally be sort of written out of the rule books, almost generations later, because nobody’s actually applied them and everybody goes, That’s just silly. We just ignore that. It does appear that the law is sometimes quite slow to react to new aspects of society, and is that your feeling that these things get formally expunged. But before that nobody’s really applied them anymore.

Daniel Shen Smith 10:13

Yes, that seems to be the case, even here. It took a long time. And it wasn’t until 1819, Lord Elder, the Lord Chancellor, introduced a bill and all of the readings were done in one night, because there’s a definite feeling that, as you just put it, this is ridiculous, it must stop and effectively it stopped overnight. Whereas abolition of the death penalty was 1965. It was sort of phased over five years and even then remained for certain things for for many years later. So that again, took a long time, law is is known to be slow to change. And whilst things do progress a lot more rapidly than they used to law is trying to catch up and keep up. So I’d like to think laws improved.

Jason Kingsley 10:55

Again, forgive me if I’m getting this wrong, but the principles of law in this country come from very early phase of lawmaking, the common law, which is the sort of decisions made by people who are deciding these things, and then you’ve got the rules that are actually written down by people who are deciding the law. And that’s in sort of stark contrast to Napoleonic law, which I think is another thing where you’ve got lots of lawyers writing down theoretical what you can and can’t do.

Daniel Shen Smith 11:24

So yes, obviously, we have common law, which is decisions made and applied to any given set of facts. So the idea being that another case comes along, that’s almost identical or near enough that that decision should be applied to the same case as it was before, then that’s that, and that’s generally the decision. And obviously, with the hierarchy of the courts, the higher the decisions, binding on lower courts, and so on. Even that’s extrapolated out with European decisions. But then when we have legislation, and this is when there’s often a lot of confusion as to whether there’s a difference between common law legislation and Acts of Parliament, whether they apply or whether they apply by consent, but with Acts of Parliament, it’s codified law. So there may be lots of decisions in a given area, for example, then there’s various regulations either brought in by our own ministers or from Europe. They are then codified, and it becomes primary law. And so it will, in some instances, override some case decisions.

Jason Kingsley 12:26

By codified you mean sort of written down in technical language in a document. That’s kind of interesting as well, because it impacts on us as martial artists, like the rule on knives, for example. I live on a farm and I use a knife all day, every day for lots and lots of different things. And so I have to be very careful, if I leave my own property that I’ve got a legal knife. Of course, some of our listeners in America may find that very surprising, because obviously, there are totally different laws there. In this country, it’s very different, I believe, nominally to control inner city violence and that kind of thing. Then there was the thing on samurai swords, and some extraordinary stuff abut ninjas. Ninjas appear to have particularly exercised the law makers a few decades ago, things like throwing stars and nunchucks. These are illegal, but they’re specially described in law, what they actually are.

Daniel Shen Smith 13:25

Yes, there’s a number of reasons for it. And there’s various categories. So certain things are just outright banned, like the throwing stars are outright banned. And there’s a list of them, which I do link to in one of my videos, and I described some of them. And as for yes, the swords, there was an outright ban at one stage, but then it’s sort of a created certain exemption. So if it’s traditionally made, or if it is an ornamental piece, then that’s okay. I often say the law is and usually should be about common sense. Most people usually tell me common sense is not that common. Nonetheless, I think a lot of law, most law, should be about common sense. If it should really be controlled, then that’s what the law should say. And the idea behind the knife laws, they are quite strict. But the idea is just to make it an offence to have a knife or something like that, where you really shouldn’t have it, where there shouldn’t be a need for it. And that’s why there is this specific defence and a small exemption, I think it is a small exemption with the folding pocket knife. But the defence is a good reason. So, you know, if you are found on a farm with a knife and you’re doing something, even if it’s not your work, or you know, let’s say it’s a public place in that instance, if it’s a very good reason, and it’s obviously a good reason, I would like to think that there is an exercise of some common judgement and good sense that you have a good reason to be there. Likewise, there’s lots of discussions around bushcraft, and lots of people say, We absolutely need to have have a knife, it’s part and parcel of doing what we do. I would like to think that if there’s a good reason in there, that’s what the law is for. Whereas if you were to contrast that with someone walking around with a 12 inch kitchen knife in a city centre, I can’t think of any possible good reasons you’d have.

Jason Kingsley 15:19

Yes. And those circumstances could change as well, because I’m aware there was a situation down in Hastings quite a few years ago with reenactors, who are performing on private land, doing it for English Heritage and reenacting the Battle of Hastings, and they have swords, and most of them are blunt. So I’m not sure whether they would fall into the category of actual swords. But, you know, nonetheless, they look quite threatening. And lots of people went to the pub outside afterwards, in kit, and a couple of people went with swords in kit. And they were seen brandishing them in the pub garden, and caused alarm, and quite rightly, in my opinion, were arrested and got into a lot of trouble as a result of it. And lots of people said, Yeah, but they were reenacting. And the point was, they weren’t reenacting in the pub at the time they may have been before. And so the issue is the context. And context is one of those important things that hopefully, the courts will analyse.

Daniel Shen Smith 16:13

Yes, they are very narrowly interpreted, these sets of facts. So let’s say you’re just storing something in a van as a matter of course, and it was always in public, because it’s parked on the street, that’s not necessarily a good reason to have it there. Whereas obviously, if you’re driving to work with it, and it’s in the van, that’s obviously a good reason. Forgotten about it is generally not a good reason. Picking up on one of your points as well, whether it’s sharp or dull, this really draws up lots of questions, because the ACT refers to the length of the cutting edge. Now, if I were to hold up a ruler to you, and say it’s got an edge, you know, a full size ruler, 30 centimetres long, if I were to sharpen very deliberately one part of it so that it’s razor sharp, but only two inches, those two inches, some might say is within the legal exemption. But of course, it’s not because the whole thing is much more than three inches and it’s not folding, and so on, and so on. So that’s been tested in court, and it was a butter knife in that case. And the butter knife was obviously not sharp, but was a blade nonetheless. And so it was held to be whereas a screwdriver was held not to be because that was just a tool. So they are very narrowly interpreted and analysed on any given situation. And as you said, if someone is reenacting, and it’s a designated event, that’s one thing, but turning up at the pub with the sword later, what you’ll expect, and I expect the courts would have looked at in that particular case was, anyone that say wasn’t part of the reenactment. If one was confronted effectively by someone in sort of full kit with a sword, you’re probably not expecting it. Even if it was obvious that they were just there, after an event, they might still be intimidated by it. And I think that’s sort of the point. It can go further than that. So if you were to turn up in town with a sword, for example, it might even amount to assault because that’s obviously giving fear of immediate harm to somebody. So, again, they all looked at on their individual merits.

Jason Kingsley 18:17

So going back to an earlier phase, obviously Magna Carta is something that has been in the news for quite a lot of reasons. And it’s beloved of certain conspiratorially minded people about what rights it does give you and doesn’t give you and if you’ve read it, which I have and I’m sure you have. It’s obsessed with fishing and fish wiers as well. But that was the first – as I’m aware of it -that was the first attempt to limit the rule of the monarch from William the Conqueror. He said, Right, all of this is mine. And I’ve got the soldiers to prove it, overriding thousands of years of of other parts of society. They wanted to try to control that because the king was being a bit random. The idea of having people judged by your peers, of course, only applied to the barons, anyway. So that fairly interesting document, although widely misquoted and misused, does it have any relevance today other than historical value? Is it still partly law in any way?

Daniel Shen Smith 19:18

Well, there’s only I think it’s four parts that are still valid today, and that 39 and 40 from memory are the most sort of prevalent today. That, of course, is trial by jury. So that prevails and that really is the main thing I would say that’s of any real relevance today.

Jason Kingsley 19:36

There was a wonderful clause in it when I last read it, which I think was about the sort of senior barons being able to come together and steal the Kings castles and goods if the king wasn’t doing the right kind of thing. I had a vision of all the barons getting together and basically stealing castles from the King. There’s a threat to somebody who came from a society where a lot of people would have believed the divine right of kings. It’s quite a brave document because it’s overriding that divine right and saying, No, the rule of – basically – us, the barons who have their own castles of soldiers. It’s the beginning of the control of that side of things. I believe it was basically annulled by the Pope – that it was going against God’s word. But it’s very interesting early document for the rise of secular rulemaking.

Daniel Shen Smith 20:34

It links with the fairly-common, recent argument of consent and being governed by consent. I think the idea probably was really kicking about then. And as you say, it then applied to the barons. But as we see it today, at its best, it’s common consent, and that, of course, is an elected government, who is then invited to form government in her name by a majesty. So that’s the modern interpretation of governed by consent, it’s a common consent in an election. You have the choice to vote or not. A lot of people don’t.

Jason Kingsley 21:11

Society revolves around consent, meaning the idea of money is an interesting one. People are talking about electronic forms of money, like Bitcoin and Dogecoin, and people go, Yeah, but then they’re not worth anything. And then I look at a piece of paper that’s printed with a 50 on it, and think, Is that worth 50 pounds? On what basis is it worth 50 pounds? The whole thing can become a bit abstract. If you look at it too much. I guess, arguably, it’s the same with the law. It’s a set of rules we’ve all agreed to. But there have been massive upheavals in societies where everybody’s gone, We’ll have to throw away this old law and start again. I mean, the French Revolution, for example, the English Civil War and Cromwell where they basically threw all the parliamentarians out, there’s not a single honest man in this chamber, they said, clear the chamber. Could you see in the future, some ‘revolution’ in inverted commas like that happening with the way the law is applied? Maybe with artificial intelligence or machine learning somehow?

Daniel Shen Smith 22:21

Yeah, well, it’s very interesting, because when I was giving this chat some thought today, I was really thinking that the way people settle their disputes today is a different form of trial, isn’t it? Where there was trial by ordeal or trial by combat, this is a different sort of combat. It’s no secret that if one were to go as a litigant in person against a ‘magic circle’ law firm with a leading barrister, he or she will stand much less of a chance in the case. Not just because they can’t research it and the costs of doing so. But as I often say to clients, and I say in some of my videos, one of the reasons you absolutely must take legal advice is because you don’t necessarily know whether or not you have a valid defence. If you are accused of doing something, it doesn’t matter what it is there may be a legal, very valid defence that means well, although you’ve done it – let’s say it’s self defence, for argument’s sake – you may not know that you have that defence unless you’ve taken legal advice. So then we do come back to the principle that if you can’t afford the legal advice, then you may well have defendants admitting guilt or things that they have a defence for. You may well have litigants in person losing cases because they don’t know how to present the evidence. I’ve heard and read in many of comments from lots of people saying that they haven’t had their evidence heard at court, because, you know, they turned up with three bundles of it on the day, and the court wouldn’t hear it. Obviously, that’s because there are rules about when it should be served, and how it should be served, what format for witness statements, specifying the size of font, for example. So if one turns up with a perfectly winnable case, but all the evidence just isn’t heard, because it’s not being served properly, and so on, it comes back to this idea, this really is a trial by a sort of non-physical kind of combat, isn’t it? It’s legal combat.

Jason Kingsley 24:33

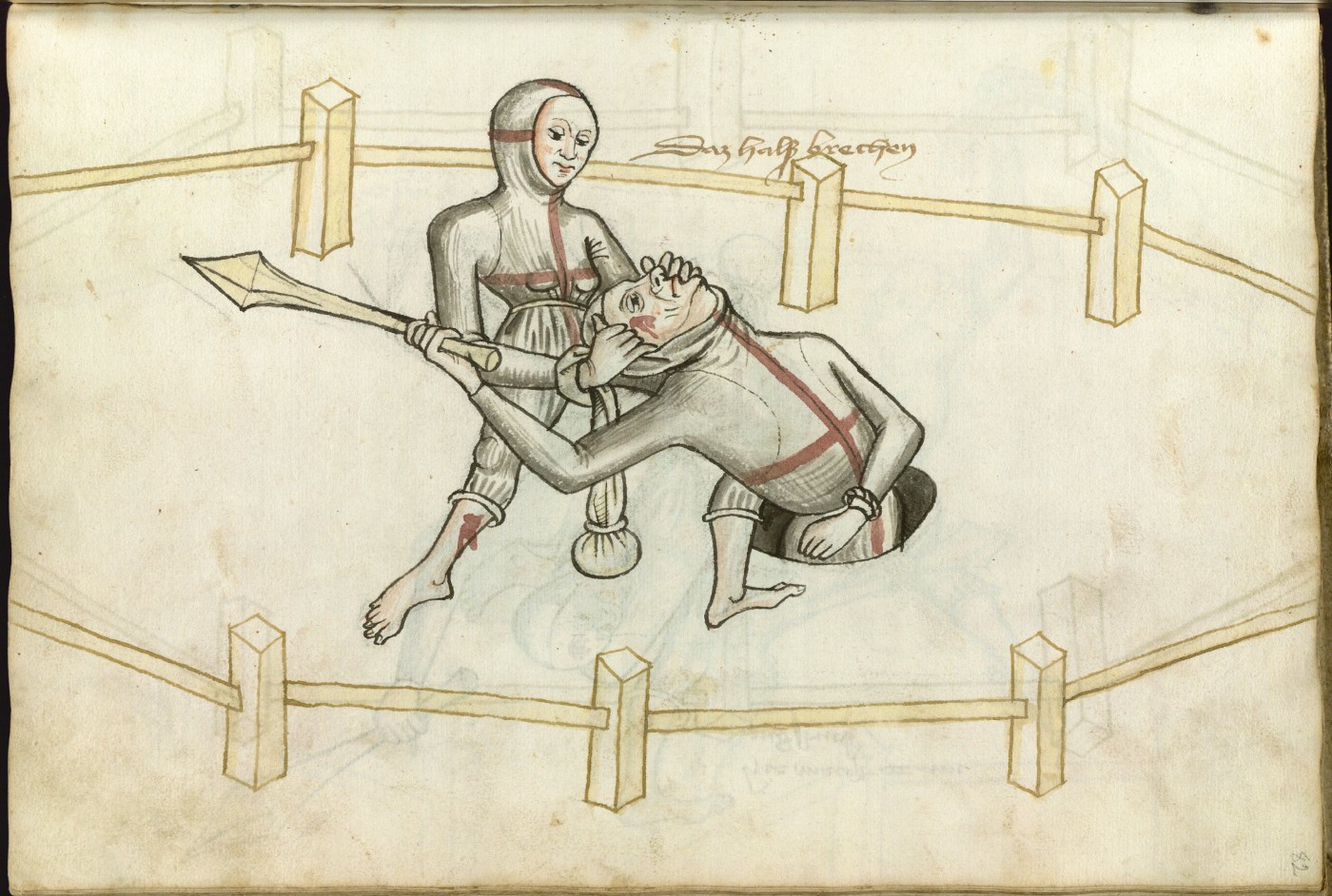

That’s interesting, because trial by combat, often you were allowed to choose a champion, you were allowed to substitute somebody else because even back in the Middle Ages, I think they believed that it was unlikely that somebody couldn’t fight could beat somebody who could fight. Even in German, mediaeval treaties, I’ve seen situations where you’re having trial by combat between a man and a woman, and they’re both sewn into leather suits and the woman has a rock in her veil. The man has one hand tied behind his back and is waist deep in a pit dug into the ground. So they obviously had some concept of making it fairer. Even if they believe that the combat would be overseen by a higher power and the right person would prevail. There are some fantastic illustrations of that, it’s absolutely crazy. I mean, how often that was actually enacted? I don’t know. But the idea of having legal representation is you’re effectively paying for champions to fight it out. Almost literally, that.

Daniel Shen Smith 25:32

Yes, indeed. It cannot be any secret that if one can afford the very best legal representation, then you have the better chance of winning against someone that doesn’t. And that is a fact. And that really is one of the driving forces behind me doing this latest channel, Black Belt Barrister, and, however cliche, it might sound, I think law should be accessible to everybody. And even though I am really just scratching the tip of the iceberg, with the videos that I’ve put out, it’s already evident that they are helpful, and everybody should have this sort of access to it. When you get deep into a case, it’s quickly clear that they can be so complex that you do need lawyers to look into it for you.

Jason Kingsley 26:18

And I think the language used as well, because the physical language of trial by combat was very organised and systematically done, there were rules about it, the people watching I mean, even things like duelling had a very strict set of rules, you know, sometimes it was the first blood, sometimes it was to one shot each. You weren’t meant to run away. In some cases, you had seconds, whose job was to make sure you didn’t run away, as opposed to look after you. You can have surgeons on hand, to immediately be there to provide medical aid. So all of these do get more and more stylized. And you could argue, I mean, once you could probably actually have a proper fighting court with your abilities. Most other people probably don’t specialise in that area. But it is a combat it’s very clearly a combat, but it’s a cerebral combat, it’s combative ideas and presentation, and how you present the idea as well, and how persuasive you can be I presume, and personalities come into it as well, I would think to a certain extent.

Daniel Shen Smith 27:19

Yes, I think so. There is a certain way of putting arguments across and it certainly shouldn’t need to be aggressive in any way. I would say, you know, legal arguments should be exactly that. It’s an argument based upon facts and law, thereby an interpretation of a judge or finding a fact by a judge or a jury, of course. And in essence, it is saying that one thing happened over another and the law either permits or prohibits what happened. Or it’s a finding of fact, in which case, you’ve either in a civil case, it’s well, who was right. And we don’t like to say it was right and wrong, or win and lose. But ultimately, that’s really what it is, and certainly with criminal cases, and one of the arguments about why we got rid of the death penalty and why we have appeals processes is because I like to say if we are going to punish somebody for doing something wrong, then we really should be absolutely sure. Whilst we have the criminal test, the burden of proof is beyond reasonable doubt. But the test given to the jury these days is phrased so that they can properly understand it so that they have to be sure of what it is that they are deciding they must be sure.

Jason Kingsley 28:39

And that’s quite a difference then. So technically, it’s beyond reasonable doubt, which means if you doubt this, you are being unreasonable, by definition, but the juries are unskilled at the law by definition. They’re ordinary people. So the idea that they’re they’re guided in how to make a decision, not what decision to make, but how to make that decision.

Daniel Shen Smith 29:04

Yes. So that’s usually going to be put across by the judge in summing up. So the judge in a criminal case, obviously, the judge will sum up the case as to what’s been proffered by each side, and then give any directions that are necessary and direction would be in the sense of what they need the decide. Judge might say that the Defence has raised self defence and said that, yes, the defendant accepts that he did this action and hurt somebody, but says that it was in self defence, and then the jury must be sure, if persuaded by the prosecution, that it was not in self defence. So there’s a shifting of this burden of proof all the time. So the defence in that example, wouldn’t have to prove that self defence is offered for that, but it must be raised as a self defence and then the prosecution must have must prove the case so that the jury sure that it was not self defence.

Jason Kingsley 30:05

Which arguably is quite a high standard, because witnesses and information and belief at the time is all quite complex. The jury has to unpick quite a lot of complex motivations. In some cases I imagine, it’s blaringly obvious. In other cases, it’s much more marginal, and therefore comes down to the jury’s opinion over it. I was actually going to ask you about alternate dispute principles and resolution, because arguably, trial by combat is a form of alternate dispute resolution. But today, we often have things like that where courts are expensive, time consuming, can take a long time to be heard. And there’s a lot of emphasis, I think, recently on trying to get the parties to reach an agreement before they ever get to court. Is that right?

Daniel Shen Smith 30:54

Yes, absolutely. And I can speak to that, because as well as being a barrister, I’m a mediator as well. So and I can say that every mediation that I’ve either conducted as a mediator or been part of either as the lawyer or observing – because we’re required to observe mediations before we conduct our own – have all settled either on the day or very shortly afterwards. So if you compare that to the process of going through court, a mediation is ordinarily conducted in either half a day or one day, whereas if they were to have proceeded to court would have probably taken another year, maybe two and probably £50 to £100,000 of costs on either side. Compare that with what the parties pay for one day. It’s infinitesimal. Absolutely, I’m a big proponent of mediation and alternate dispute resolution.

Jason Kingsley 31:43

And it’s forcing people to actually confront the issue and get it solved and get it out of the way because things hanging over you can impact quite dramatically on your life, because you just haven’t had a resolution. Sometimes living without a decision can actually be really quite traumatic for people.

Daniel Shen Smith 32:00

That’s the thing, it’s living with it. You’ve hit it on the head, really. It’s something that parties will have to live with 24/7. Most people that I’ve come across, most clients that I’ve had, that’s the one thing that drives them to any kind of resolution is the fact that they wake up and it’s the first thing they think about, and they’ll randomly think about it during the day and then it’s the last thing I think about when they go to bed. When they get a letter through the post, they panic, that it’s a letter about this, and an email or phone call, and so on. That’s even the case whether it’s a couple of thousand pounds, maybe or even less, in some cases. I’ve had clients get just as worked up over a few hundred pounds worth of a claim that’s going through. With the backlog in the courts as well, I’ve had small claims take probably a year to a year and a half to go through court. It’s a long time for somebody to be tied up in the process. And the process isn’t necessarily much more straightforward, just because it’s small. There are some simplifications. One of the big ones is costs. So if we’re talking monetary claims, a claim not more than 10,000 pounds, generally parties are not at risk to costs other than fixed costs – issue costs and hearing costs and things like that. But that just takes out some of the pressure of paying lawyers. But then of course, if parties wants to pay lawyers, they can’t ordinarily claim those back unless there’s been unreasonable behaviour on the other side. And it still winds them up for a long time. Whereas a mediation, it’s over and dealt with.

Jason Kingsley 33:38

Yeah, and even if you lose, that can be quite a relief, because at least it’s done and dusted now. You can be angry about it, but it’s solved and you can move on. But I was going to say the idea that one of the ideas of Magna Carta was that justice should not be unduly delayed either. And one wonders whether they imagined taking a year and a half to two years to reach the court would fall foul of those provisions of delaying, because I believe in mediaeval period, depending on which period you’re looking at, the courts used to actually travel around, and there might be one big quarter year in a town and everything has to sort of save up for that and all be heard at the same time.

Daniel Shen Smith 34:14

Yes, well, that’s where the circuits come from. So you know, the southeastern circuit and so on. So they were a circuit were initially the king, obviously, and eventually others were going around on the circuit to hear these cases and make decisions and those terms survive. moot was the original term for court. And now it’s used as a as a mock trial. And so yes, they were moved around and the principles of speediness and expedience, they do survive today. It is simply a matter of the number of cases going through the system. Of course, with the pandemic hasn’t helped much. With so many tens of thousandss of cases in the backlog. They are just taking time.

Jason Kingsley 34:55

Yeah. So if you were doing alternate dispute resolution could the two parties agree to have a fist fight over? Who was right and who was wrong? Or would that not be an acceptable solution?

Daniel Shen Smith 35:10

Well, no. I mean, the idea being, how would you judge it? If you were judging it on some kind of injury coming out of it, you couldn’t consent to some sort of injury in that sense. I mean, I suppose there’s some merit in looking at other ways you could resolve it. Now, of course, one of the big benefits of alternate dispute resolution is it’s much more flexible. If you put it this way, if you get a judge, the way I try to explain it to clients is that when you go to court, you’re effectively asking the court to make a decision, because the two of you can’t. And that’s really as simple as you can make it. And so when you ask the judge to make a decision, then you’re asking for a remedy. And really, that there’s only a handful of remedies. The biggest one is money. Because it’s an amount of money that compensates or put something right, you know, either fixes a roof or compensate somebody from, let’s say, being disabled for the rest of their life. Obviously, stark difference between the two, but the only real way a court can judge that is awarded amount of money that helps. But what if a party just wants somebody to apologise now a court can’t and a court won’t order that.

Jason Kingsley 36:20

Okay, so you can’t be made to apologise, know

Daniel Shen Smith 36:26

I always use the example of roof because you know, if a roof’s leaking, you might as well not have a roof. I often think that if you’ve had a really bad job of a roof done, a court could order the company to come back and fix it. But because the relationship between the parties is probably torn down by now, a court is not likely to order that. A court is likely to say, Well, what’s it going to cost to repair it, you know, another 1000 pounds 5000 pounds and award that instead. Then the party with the bad job can pay someone else to get the roof done. In theory, a court could order the return to fix the roof, but probably won’t. But when it comes to an apology, No, a courts not going to order that. Whereas in alternate dispute resolution, Yeah, of course, they can agree with an apology. And that in itself can become a binding contract. So what they do is they form up in the case where there’s live proceedings, they draw up what we call a Tomlin order. It’s like a consent order, where parties are agreeing to bring the proceedings to a close on a set of agreement that they’ve reached between each other. Often it’s in a schedule, so it’s not actually filed with court. So it remains confidential. And parties can agree in essence, anything they like, very often, in fact, where let’s say two businesses have majorly fallen out over contract terms and payments and so on. Very often, they will agree to new terms, new contracts that they hadn’t even discussed before, but it forms a new contract to settle the existing dispute. And any disputes that arise out of the original facts. Again, there’s no way a court could possibly get involved in that.

Jason Kingsley 38:05

So in many ways, the sort of formal court system is less flexible in outcome than than the alternate dispute resolution.

Daniel Shen Smith 38:14

It’s not to say it doesn’t have a use, obviously, because parties don’t always wants to settle. It may not always be possible to settle, they do want an outcome. I’m not going to use any particular type of company or organisation as an example. But if you had an organisation that simply refused to cooperate or settle or whatever, but there was clearly a wrong, then it’s only right that there is a mechanism of a third party judicial intervention to say, No, this was wrong, this individual or whoever deserves some compensation because of the wrong and only a court can award that.

Jason Kingsley 38:51

A question more about sort of mediaeval law and that kind of stuff for your memory, what’s the oldest practical law that still used or mentioned in court? Is there one everybody knows about?

Daniel Shen Smith 39:10

Right? There’s quite a few. I mean, the one that springs to mind as you said, it was the Offences Against The Person Act 1861. So, again, in the comments that I get on my videos, a lot of people will say, Well, this is really old law, we should replace it and update it. But my response to that is, Well, it is updated, but the basic principles are still there. So offences against the person is what it sounds like, it’s an offence committed against another person. So it’s some form of harm. And so you have this hierarchy of harm within those. So whilst this is an old law, you might say there will be older and many, many cases go back earlier than that. They are common law precedents that survived today and are still used today, because they’re still good law. Again, it comes back to common sense. Some were very solid decisions albeit made a long time ago. A lot of them are shipping cases.

Jason Kingsley 40:06

Maritime law is very, very old, isn’t it? One of the oldest branches of law, I believe.

Daniel Shen Smith 40:13

Yes, I believe so. Obviously, lots of those decisions will be based around shipping delays: who’s responsible? Because when you get into these sort of hypothetical scenarios, you can really find some difficult decisions to make. Who’s responsible for the goods? Let’s say, Party A is in one country and Party B is in another country, but it’s going to take – in those days – maybe a year to get the ship there? Let’s say it’s sunk halfway, or it was hijacked? Who’s responsible for it? Who do they belong with?

Jason Kingsley 40:45

Who takes the loss? Who’s lost what and who’s to blame for it, even if, arguably, neither party is to blame? Because the ship was attacked by pirates. But somebody has to take the blame in the commerce. That’s interesting.

Daniel Shen Smith 40:57

Yeah, so lots of those decisions survived today, because they’ve just come before the courts they’ve been examined in those that are, and some of them are just such overarching principles, that they don’t really change too much. Things such as giving notice, you know, so we have the postal rule when things are posted. And, you know, these days, lots of people sort of insist on sending something by special delivery and registered posts and everything else, which is good to see that it’s tracked, but actually just sending it in ordinary post is still deemed to be good service today.

Jason Kingsley 41:32

So one of the things I was going to ask you is, is especially during a pandemic, people have not been doing things in person, things like signatures. The signature or seal. Obviously, back in the day documents had to be sealed. I believe that stamp duty comes from the need for the King to take a piece of tax on every transaction. And he basically said, this document is not legal unless I’ve got the stamp on it, which is my piece of the pie. Basically, the king wants his piece of the pie. And you see things like Magna Carta, and some of the Charters of the Forest. And they often have seals, wax seals that represent knightly characters and that kind of stuff. I presume a signature evolved from people making their mark on documents?

Daniel Shen Smith 42:26

Yes, and then there’s been lots of discussion over what constitutes a signature. Certainly, at one point, an electronic signature was not a signature in the eyes of the court, whereas it is now. And then there’s been arguments as to whether it was a handwritten signature, albeit electronic, as opposed to typing your name at the bottom of an email. So now, typing your name at the bottom of an email is good enough to say that, it might as well be your signature, you’ve effectively signed your name before sending it. But as you mentioned, the pandemic, one thing I had to look up was whether or not deeds work like that, because of course deeds do need to be witnessed in person. Then there’s a whole discussion because of everybody working remotely, is it okay to have somebody remotely witness a signature over Zoom? Or whatever? All my research came to the point, probably not. But actually, if you know, if parties are going to agree to it, then it might well be down to the parties. But there’s certainly an argument.

Jason Kingsley 43:29

That’s interesting. So the concept of physically being in the same space is different from physically witnessing, because you can imagine being in the same room watching somebody sign is one thing. So you could then abstract that one level and say, I’m in a different room, looking through a window, that probably still counts as witnessing the signature, but you’re not in the same room, then you could abstract and say, but I’m looking at a camera that’s looking at it. And that isn’t potentially witnessing. Yes. And so therefore, this is some difference in law. Conceptually, I can see it, but it’s kind of narrow, isn’t it? The difference between looking through a piece of glass and looking through some electronics is sufficient to make it different in the eyes of the law for the moment, because presumably, there could be a court case that would then change that. And it would then be sorted out one way or the other.

Daniel Shen Smith 44:23

Yes, there’s various rules. I mean, CCTV’s the example. There’s various rules about an officer witnessing something via CCTV and when that’s admissible, whether they can amount to be a first person witness and things like that. Then of course, a lot of the arguments are always going to be around whether it was good enough quality and for some reason, you know, most people take out a phone and it’s HD and you can see everything in perfect clarity. As soon as you get to CCTV. It’s tiny, monochrome and pixelated so you can’t really see anything.

Jason Kingsley 44:58

I mean, there’s some interesting stuff there in terms of the way that artificial people are being generated. Obviously, there’s lots of issues over the reliability of human witnesses, people can be very mistaken. There’s a fantastic psychology experiment I saw once with a video and they asked the question, how many times is this ball passed between these groups of people? And then at the end, they go, And did you see the man in the gorilla suit walking past? I have to say, I didn’t see the man in the gorilla suit until I rewound it and went, Ah, how did I miss that! So people’s perception is always open to interpretation. People see faces in flock wallpaper and tea stains and that kind of stuff. Human brains have evolved to look at threats in an interesting way. Therefore, the court has got to unpick that and try to work out whether frightened witness number one is actually at all reliable, or super brave witness number two, who definitely saw a totally different person is reliable. That’s also quite difficult to do, because both witnesses may honestly believe that they saw the truth of the matter. But their witnessing is not necessarily the same.

Daniel Shen Smith 46:10

Absolutely. As an interesting story, actually, my very first work experience was with a queen’s counsel in one of the chambers in Birmingham. Obviously, I was 15 or 16, at the time, and I went in and, you know, said, What’s the best way to get an idea for what this kind of work is like? I suppose it’s a bit of an unusual question. But he gave me a stack of documents. He said, just read those. And then you’ll have an idea. What it was, was a stack of witnesses about a big brawl that happened in Birmingham. And each one was obviously two or three pages long and there’s probably close to 30-something witnesses. Each one was a very, very slightly different account of the group of people fighting. And I was writing down the descriptions of each person until such a point that I realised this is nonsense, because there was so many different perspectives and points of view, no one can be sure what happened if they all turn up to give evidence, because it was so different. But they all genuinely believed enough to commit to a police statement and sign in. That’s what happened.

Jason Kingsley 47:17

That’s why the courts have always had to try and interpret the human side. I suppose why they mostly arguably get it right, but sometimes get it wrong. Just looking back through some of the minor courts in the mediaeval period, in particular, and the things that bothered ordinary people, not so much kings and barons, but things like people’s pigs escaping into their garden eating their turnips, or people’s cesspits, that the mediaeval period seems obsessed with cesspits. Cesspits often collapse, aren’t emptied, are filled in, or dug too close to the boundary wall. I was thinking, these are all very, very human scale issues, that still affect us now. The neighbor’s fence falls down. And it really annoys us to the point of distraction, in the grand scheme of things historically, is make much difference. Your empires are not going to fall over the collapse of a fence. But it means the world to the people involved. And it’s really important that it’s solved. But it’s absolutely fascinating with the exception of livestock escaping, you could just change the names change the settings, and there would be modern magistrate courts.

Daniel Shen Smith 48:30

Funnily enough, I actually started on TikTok, believe it or not, as probably the only barrister on there to begin with. Some of my first videos were about garden law, because probably like everyone else working from home realised more about the garden than we probably ever did before. Lots of arguments about lots of inquiries were coming in about, My neighbours doing this, my neighbours doing that? And what about this tree? And what about the roots and, and so there’s, obviously there’s lots of rules around that as well. What we’re really talking about going back with this, the cesspits and escape of animals, and essentially, they come to some kind of nuisance or another, and some kind of trespass or another and some kind of easement or another which is obviously one land having some kind of right, or priority over another, or profits or ponder is another phrase where one land might have the rights to take something for benefit from another land. Let’s say if it was, you know, fruit or vegetables available, and it was supposed to be common to various areas, each of the surrounding land had the right to take the food from that place. So you’ve got these arguments. And you’re right, that you could just switch out the fact that it’s this escape of, you know, pigs or whatever, to someone having a gas flue pointing at your property, which now obviously, we’ll have building regulations as to how close it can be, how wide it’s got to be, how high off the ground, it’s got to be and so on. So the law tries to cut off each of these elements of difficulties that people have and isolate responsibilities. Who’s responsible for what?

Jason Kingsley 50:12

Even in the mediaeval period, this book of nuisances, I was reading the courts actually ruled against members of the nobility from time to time. There’s one particular case where it appears that the the lady of the manor wanted to extend some buildings, and the good people of the town said, But we won’t be able to get our carriages, our carts around that corner, if you do. They said, You can’t build an extension to your house. I thought that was kind of interesting, because it clearly shows that there was an assertion of the value of society at large over the nobility, over the wealthy and moneyed class. I thought it was interesting because you don’t typically think of socialism in its modern sense back in the mediaeval period, but in fact, there were very strong rules to limit and control and manage that kind of behaviour, especially when you look in the court records, you can see very clearly people saying, No, you can’t do that, that will be bad for everybody. I guess modern courts are trying to do the same. They’re trying to keep a lid on exploitation to a larger extent.

Daniel Shen Smith 51:19

Yeah. I think it’s also enshrined and rolled out locally with local authorities. Let’s say – I’m not a planning specialist by any means – but if we look at, say, planning regulations and planning law, there’s the overarching law that is then applied locally by local authorities. They set up their own planning portals and things like this, and guides as to what you can and can’t do, the amenity and having the streets effectively look the same all the way through. If you’ve got a row of detached houses, you couldn’t have someone just build a block of flats that just was completely out of character in proportion with everything else. Because it doesn’t look the same, and it affects the amenity of the entire area. There you get the distances of how far away properties can be and things like that.

Jason Kingsley 52:12

Just to summarise then, trial by combat is no longer a valid thing to bring up so I stand no chance whatsoever of having an argument somebody getting right, I’ll fight you. That’s disappointing, but understandable. I suppose.

Daniel Shen Smith 52:27

There was somebody did try it. I think it was 2002. I think he was given a fine of £25 and turned up at court and tried to exercise his ancient right to trial by combat, it didn’t work, it actually trumped up his fine. I think he got fined £200 with costs on top of his efforts.

Jason Kingsley 52:46

A for effort there. I would encourage that. No, I wouldn’t encourage it, because it’s a waste of time. But it’s quite astonishing that people would go to court in that sort of serious official way and genuinely claim that I mean, it’s not even the place really to make jokes, I wouldn’t have said but you know,

Daniel Shen Smith 53:03

Absolutely not. And not to make threats, either. Whilst many, many of us have been in practice much longer than I have. But even while I’ve been practising, I would say at least once a month, I’ve seen somebody dragged out of court for shouting and arguing with the judge. Right? It does baffle me, honestly, because I just think this is not right. It’s not civil. And in any event, it’s only going to end one way. And so they’ll be removed from the building. So I encourage everybody to be civil with everybody else, even though you might well be arguing with somebody, I think one of my recent videos, I say that a consumer is not always right. This old saying of the customer’s always right. No, actually customers not always right. And it certainly doesn’t give anyone the right to be rude and disrespectful.

Jason Kingsley 53:56

Yeah, I mean, there’s a whole other area we could talk about, maybe we should do another one about entitlements and how people feel that the world should revolve around them and where that comes from. But I think for now, I think we’ve had a really nice ramble through. We’ve touched on Magna Carta, conspiracy theories and trial by combat in an interesting way. I’m going to have to do a bit more digging into trial by combat because I would love to find out when it was officially abandoned.

Daniel Shen Smith 54:22

I can point you in the right direction. I haven’t read it. So I can’t profess that I have but the late Sir Robert McGarry wrote a book, a New Miscellany At Law in 2005. So that would be I think, the first thing I would go and read and now I’m even more intrigued to go and read it. Apparently, there’s a certain level of humour inserted into it as well. So I look forward to reading that.

Jason Kingsley 54:47

Brilliant. Was there anything else you wanted to let our listeners know about before we draw this to a close? Anything we’ve forgotten to mention that you want to bring up?

Daniel Shen Smith 54:56

I suppose I would leave people with the sentiment that anyone that is in any kind of dispute with anyone else there is always a civil way to resolve it. Obviously I’m not talking about criminal trials. In everyday dispute there is a civil way to deal with it. We run with the motto: no opinions, no emotion and just deal with it civilly. If anyone wants to learn any more here any more, any of my thoughts, obviously, check my channels out, and I’m happy to respond to questions and make new videos as I have done. I’ve made videos in response to questions and comments. I’m happy to do that.

Jason Kingsley 55:32

Excellent work. Really good to know. And then at some stage, we should delve into your martial arts background a little bit as well and have a whole conversation not about law, about martial arts, but historic European Martial Arts and all of that area because I think that’s fascinating as well.

Daniel Shen Smith 55:46

That would be a whole conversation. Bye.

Jason Kingsley 55:49

For now, we’ll leave it there. Thank you very much. It’s been an absolute pleasure.

Daniel Shen Smith 55:53

The pleasure’s mine.